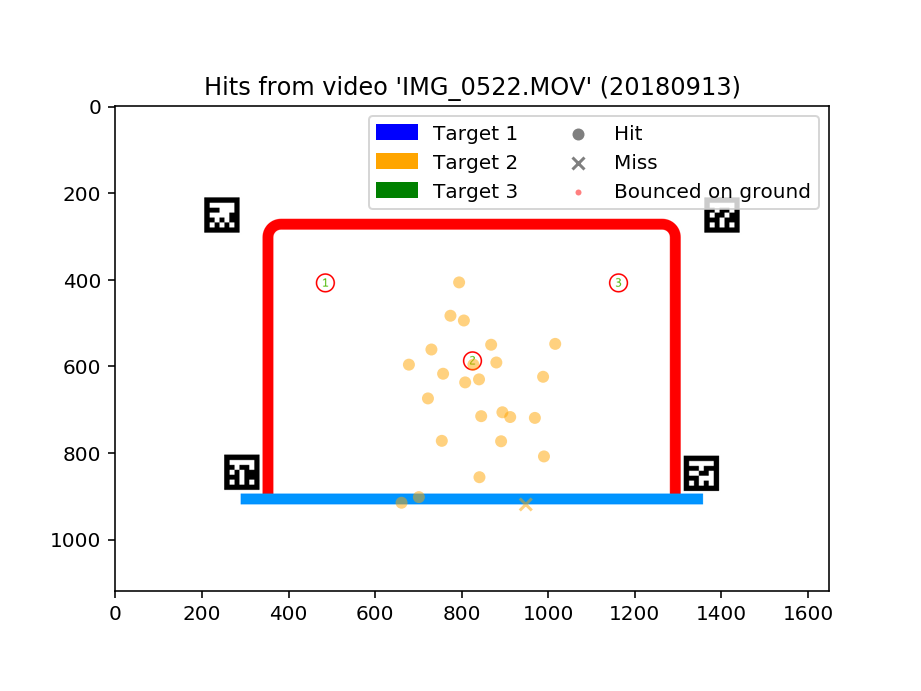

Manual positioned hits

After having analyzed 1625 shots in total (phew!), here is a compiled PDF of each round (missing the session from October 1, which I haven’t had time to analyze yet).

The long-term idea is to visualize this data in a more meaningful way for a player (like myself) trying to learn how to shoot. One thing that is painfully obvious after having manually positioned all these shots — becoming good takes a long, long time!

For each shot, I record the following information:

- The hit position. For shots outside the canvas, I approximate when the puck crosses the canvas plane and record the position at that time. Some shots bounce sideways off the ground or other pucks so never reach the canvas plane, here I do not wait until the pucks come to a standstill but record some (reasonable) position along the way.

- The hit time/frame. On which video frame did the puck hit (or miss)? Initially I tried to always identify the very first frame where the puck touches the canvas. Lately, I err on the safe side as it can be very difficult to say for sure when there’s wind, shadows, light reflections, etc. at play. Also, see below.

- Hit or miss. If a large enough area of the puck is within the goal frame, then I record it as a hit, otherwise a miss.

- Good reference or not. Is the recorded hit frame useful as training material for, say, a neural net? Perhaps the puck just barely touches the canvas so it provides a poor example, then I mark the hit frame as a questionable reference (so it could be used if I change my mind later) and mark the next frame as the proper reference. I also mark the preceding frames as reference “not hits”.

- Bounced first. If the puck seems to have bounced off the ground before I recorded its position, I mark it as having bounced. This because (a) the hit position should be taken with a grain of salt as the movement after bouncing can be erratic, (b) the power of the shot is often reduced which makes the hit a bad representative in terms of machine learning.

- Target. Which target was the player trying to hit? For practical reasons, I just use a repeating sequence like 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3 rather than a random sequence. This is not optimal for actual training but makes little difference here, at this stage.

Over time, while analyzing the videos and seeing all the different edge cases, I have realized that some of the recorded information is captured for multiple purposes, not necessarily sharing the same goals. That is, the material needed for training could be slightly different from the material needed for validation and testing.

Also, it is so easy to lose track of the end goal and make suboptimal choices: identifying the hit frames is just a proxy for determining the hit positions! Sure, here we might need references for when a puck hits to test against but in the long run, the only thing that matters is being able to accurately find hit positions.

It is likely that I need to go over the material again and reclassify as the assumptions I started with could be proven incorrect during the course of the project. The most fundamental such assumption is that all hits are to be included where I am more and more leaning towards that there must be a cutoff. If it comes down to a choice between accurately positioning all proper shots with risk of misclassifying all poor shots and, say, rough positioning of all shots including the poorest, then I think the prior makes the most sense.